Cash News

PM Images

By Joshua J. Myers, CFA

Since the Federal Reserve’s historic rate hiking campaign and the inversion of the yield curve in late 2022, we have been waiting for an economic downturn. We have yet to see one, and this has confounded economists everywhere. The lingering effects from the COVID pandemic have certainly made this cycle unique. But there are other forces at work, slower moving but potentially longer lasting, that explain the divergence between the economy and traditional economic indicators.

For one, the process of credit formation has changed dramatically in a relatively short period of time, which is a hidden but powerful force on the broad economy. The private capital markets – including venture capital, private equity, real estate, infrastructure, and private credit, among other asset classes – have grown more than threefold over just 10 years to nearly $15 trillion today. While this is just a fraction of the $50.8 trillion public equity market, the public market is increasingly including investment vehicles like ETFs and is more concentrated with large corporations that are not representative of the broader economy.

The Allure of Private Markets

Rolling bank crises and public market volatility have allowed private capital markets to take market share by offering more stable capital to borrowers and earning outsized returns for their investors by charging higher rates for longer-term capital. Investors seeking to maximize their Sharpe ratios in a zero-interest rate monetary policy world over the past decade found the best way to do so was by locking up their capital with managers who could access uncorrelated and above-market returns. An unintended consequence of doing so, however, was to weaken the causal chain between traditional economic indicators like the yield curve, an indicator of bank profitability, and the real economy because banks and other traditional capital providers are no longer the primary source of capital for the economy.

This shift has increased the diversity of capital providers but has also fragmented the capital markets. Borrowers have more options today but also face challenges in finding the right capital provider for their businesses. This greatly increases the value of the credit formation process, which matches lenders and borrowers in the capital markets and has traditionally been performed by Wall Street firms.

After the repeal of the Glass-Stegall Act in 1999, large banks and broker dealers acquired each other or merged. The impetus for these mergers was to access the cheap capital from depositors and deploy that in the higher-margin brokerage business. This ended up introducing too much volatility into the economy, as seen during the Global Financial Crisis, and regulations like the Dodd-Frank Act were put in place to protect depositors from the risks of the brokerage business. Wall Street firms are notoriously siloed, and the increased regulation only served to complicate the ability of these firms to work across business lines and deliver efficient capital solutions to their clients. This created the space for private capital firms, who also enjoy less regulation, to win clients from traditional Wall Street firms due to their ability to provide more innovative and flexible capital solutions.

The Trade-Off

The demand for uncorrelated and low-volatility returns from investors necessitated a trade-off into the less liquid investment vehicles offered by private capital markets. Since the managers of these vehicles can lock up investor capital for the long-term, they are able to provide more stable capital solutions for their portfolio companies and are not as prone to the whims of the public markets. This longer time horizon allows managers to provide more flexibility to their portfolio companies and even delays the realization of losses.

This means that public market measures of implied volatility and interest rates have less meaning for the broader real economy, because they only represent the price of capital and liquidity from firms that operate in the short-term like hedge funds, retail investors, and money managers. The cost of capital from real money firms like pension funds, endowments, and insurance companies is better represented in private capital markets.

The result is that we have substituted liquidity risk for credit risk in the broader economy due to the growth of private capital markets. When interest rates are low, the future value of a dollar is worth more than the present value of that same dollar. This lowers the natural demand for liquidity and increases the capacity for credit risk, which delays the ultimate realization of intrinsic value. Narratives come to dominate investment fundamentals in these environments.

The Changing Playbook

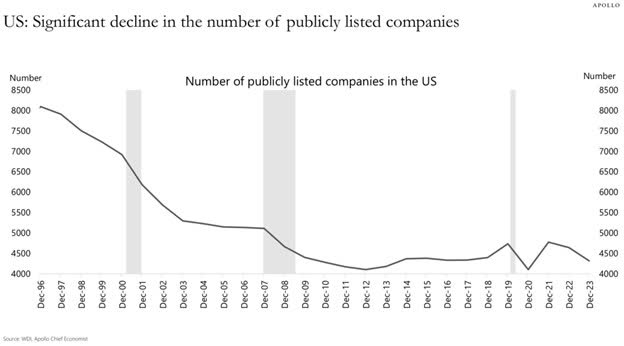

This changes the playbook for companies in how they fund and grow their businesses. Companies can stay private for longer as they increasingly find long-term investors in the private markets and do not have to be subjected to the higher costs and strictures of the public markets.

Source: @LizAnnSonders

The M&A playbook has changed, the universe of publicly traded companies to take private has shrunk, and the marketplace for financing these transactions has changed. In the past, a Wall Street bank might have offered a bridge loan for an acquisition to be followed by permanent capital placements. Today, acquirers can partner with hedge funds, private equity, and family office firms for both short-term and long-term capital in a form of one-stop shop for corporate financing.

Looking forward, as the popularity of the private markets increases, there will be an inevitable agitation to democratize access to these attractive investments. However, enabling the masses to invest in these sophisticated strategies requires increasing their liquidity, which in turn will impair managers’ ability to provide long-term capital and delay fundamental realization events. This will result in a reversal of the credit and liquidity risk trade-off we have seen recently and eventually re-establish the link between the traditional public market-based economic indicators and the real economy.

Disclaimer: Please note that the content of this site should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.